So to recap from part 1 of this post, the problem I am chewing over is how can I, as a budding realist painter, find myself so moved pictures which falls short in many criteria that realists are supposed to master? And secondly, how should I incorporate this awareness into my practice in the future?

I can’t help but reflect that it seems that there may be some point where realism, by its very nature, comes into conflict with poetic expression. I am not sure about this and I certainly can’t prove it but my experience tells me I feel it to be true. It may just be a matter of temperament but I know at least I am not the first to have such thoughts.

In the nineteenth century it seems to have been widely accepted and consequently we find that for critics and artists alike the realist school was opposed, sometimes diametrically, to the romantic.

Realism meant a subject matter concerend primarily with earthy, mundane (in the strict sense of the word) subject matter best encapsulated by Courbet’s comment that he couldn’t paint an angel becasue he had never seen one, and painted in a technique which in turn often insisted on the materialistic nature of paint itself.

Prose, we are to understand, is not the same thing as poetry and not designed to have the same effect on the reader.

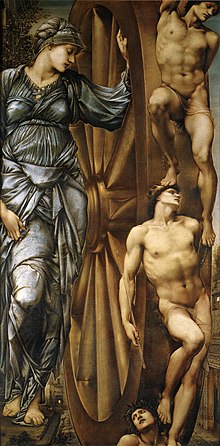

Now, against that, there are obviously many realist painters who by their sensitivity and delicacy produce works than can fairly be described as poetic, and in whose hands hard won technical accomplishments are used to produce movingly beautiful works. But, as Walter Pater famously remarked “all art aspires to the condition of music” and music being the least realistic art form I come back to the question of whether realism is capable of inducing the highest type of aesthetic response. Recently I was re-reading Ruskin’s lectures on English Art given at Oxford in 1882 and he contrasted the “realistic school” epitomised by Rossetti and Holman Hunt with the “mythic school” of Watts and Burne-Jones. Now Ruskin had made his name exorting artists to study nature attentively and minutely but nonetheless he was aware of this dichotomy as the following passage reveals.

“So long as we have only to deal with living creatures, or solid substances,

I am able to tell you — and to show — that they are to be painted under certain optical laws which prevail in our present atmosphere ; and

with due respect to laws of gravity and movement which cannot be evaded in our terrestrial constitution. But when we have only an idea to paint, or a symbol, I do not feel authorized to

insist any longer upon these vulgar appearances, or mortal and temporal limitations. I cannot arrogantly or demonstratively define to you

how the light should fall on the two sides of the nose of a Day of Creation ; nor obstinately demand botanical accuracy in the graining of the wood employed for the spokes of a Wheel of

Fortune.

Indeed, so far from feeling justified in any such vexatious and vulgar requirements, I am under an instinctive impression that some kind of strangeness or quaintness, or even violation of probability, would be not merely

admissible, but even desirable, in the delineation of a figure intended neither to represent a body, nor a spirit, neither an animal, nor a vegetable, but only an idea, or an aphorism

The quote is, I think, worth giving in full as it puts the issue so clearly but as a consequence this post is, I am afraid, inexcusably going to slip over into a third part, so I will leave the vexed issue of how this thinking may or may not manifest itself in my own work or the last section of this trilogy.